She Never Stood a Chance

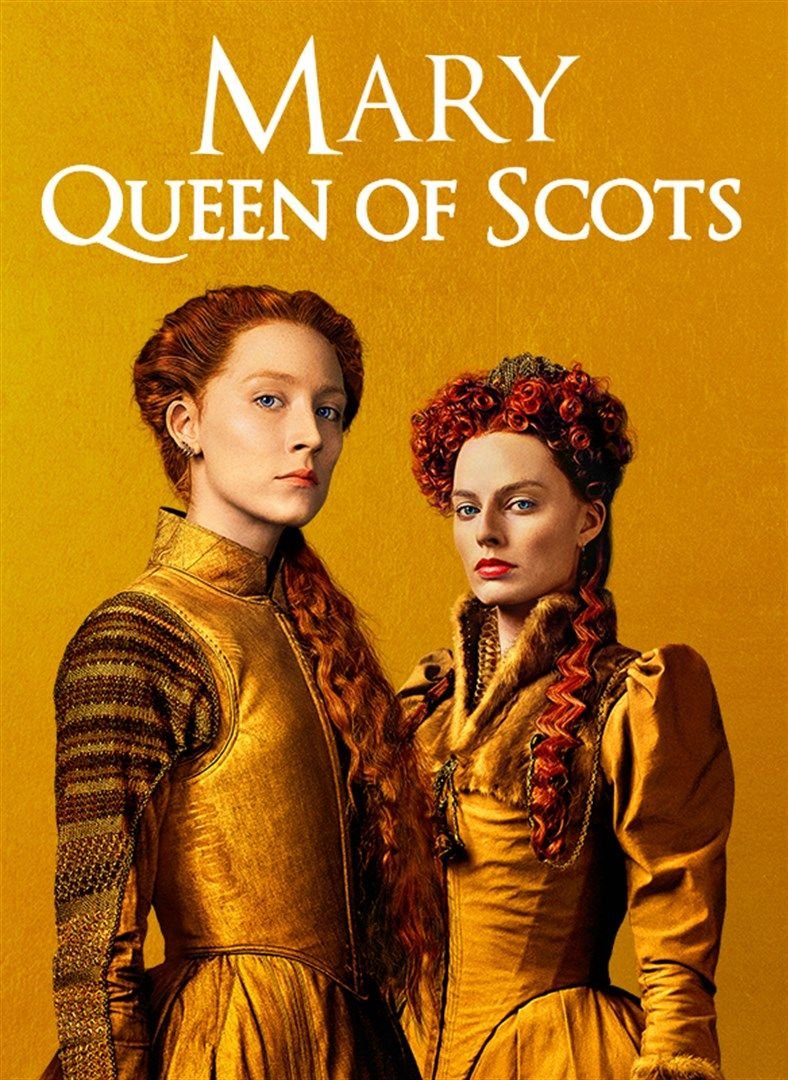

Mary, Queen of Scots: the True Life of Mary Stuart by John Guy – 5 Stars – impeccable research

I’ve read numerous books regarding 16th century British history, but this one stood out among the rest, because I discovered some fascinating facts about the Scottish ruler. While many of us are familiar with Mary, and her ongoing “feud” with Queen Elizabeth I, one thing I formulated was that Mary never stood a chance, dealing with the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants, feuds among locals in Scotland, including Mary’s half-brother Moray, and politics abroad, with emphasis on England and Queen Elizabeth’s chief advisor, the duplicitous and conniving William Cecil.

Mary Stuart was left as the only child of King James V of Scotland and his French wife, Mary of Guise, after both her brothers died shortly after their births, one year prior in 1541. The death of her father six days after her birth resulted in Mary becoming queen of Scotland in her own right, with her mother filling in as regent, until Mary obtained legal age. Although her great-uncle, King Henry VIII of England made an unsuccessful effort to secure control of her (Mary inherited Tudor blood through her grandmother, a sister of Henry VIII), the regency of the kingdom was settled in favor of her mother.

Mary was sent to France at the age of five and was promised in marriage to Francis, the eldest son of French King Henry II and Catherine de Medicis, and became learned in many subjects including the languages of Latin, Italian, Spanish, Greek, and of course French, which became her mainstay. She also excelled at hunting and dance and loved poetry and the classics. In 1558, at the age of sixteen, she and Francis (age fifteen) were married at Notre Dame. However, she was thrust into the role of Queen of France, when her father-in-law, King Henry II, died suddenly the following year, leaving his young son as the new monarch. If that was not a whirlwind in and of itself, she soon became a widow at the age of eighteen when her young husband died a horrible death due to tuberculosis and complications within.

During her time in France, she fell under the unscrupulous political yearnings of the Guise family and their never-ending quest for control of power. Unaware and naïve, she had no idea of the calamity that would ensue, as they began toting Mary as the Queen of France, England and Scotland, much to the consternation of Queen Elizabeth, who began her rule in 1558.

Mary, by virtue of her Tudor blood, was next in line for the throne, should anything happen to her first cousin, Elizabeth – something that would be abhorrent to now Protestant England (thanks to Henry VIII) because Mary followed the leanings of France and its official religion of Catholicism. Elizabeth utterly refused to acknowledge Mary as her heiress (a point of contention during their entire lifetime). It was an inauspicious beginning for Mary, even before she ever returned to Scotland in 1561.

Now home, she discovered that the once Catholic Scotland, had been reformed, due to the influence of men like leading preacher, John Calvin. Not only that, but Scottish nobles were engaged in bloody feuds and self-concerns and had no interest in supporting the crown, so she entered into a county filled with turmoil with no end in sight. However, Mary relied on her keen senses and established a policy of religious tolerance, and did win over many of her now trusted advisors.

Meanwhile back in England, Cecil and his cronies never ceased to intrude on the comings and goings of Mary, Queen of Scotland (there were also periods of warfare between the two countries). While Elizabeth’s ire with Mary would raise its ugly head from time to time, she felt a kinship with cousin and fellow queen, often forgiving her, writing letters trying to come to terms and reach an agreement between England and Scotland. However, Cecil was unflinching and if anything, he aspired to bring her down by any means necessary, installing a network of spies throughout the empire. And it would always be a point of contention between the British queen and her right-hand man.

One thing England tried to finagle was its pursuit of a suitable husband for Mary, (something she wholly resented as queen). Not that they were concerned in finding a lovable mate for her, but rather they needed someone to stymy her quest to succeed Elizabeth, if the situation arose. It was a purely political notion – one that was common at the time. What could they gain, while the other party lost something in the making? But what happened next not only backfired for England but set the wheels of disaster in motion for a normally rational and wise Mary.

Long story short, she married her cousin, the young and impetuous, Henry Stuart, Earl of Darnley, who was known for his playboy antics and drunkenness. However, he put on his best behavior, luring her into a disastrous marriage, one which England tried to stop because their bond would once again move Mary back into the line of succession. Once into her heart and bed, he became intolerable, jealous and controlling, not only making her regret her decision, but he angered enough of the nobles, including Mary’s half-brother, which unbeknownst to her, led to a successful plot of assassination. Now left alone with a child, and a kingdom in turmoil, Mary made another terrible and foolish mistake, one that led to her downfall and eventually her losing her head.

In a series of questionable and strange encounters, including the kidnapping of Mary by James Hepburn, the 4th Earl of Bothwell, she nonetheless married him, confessing that she was afraid for her life and the stability of her kingdom, therefore she did what she thought was necessary. Many felt (including the author of this book) that her extremely poor health also led to her inability to make wise decisions at the time. And mind you, James was one of the scoundrels who instigated and helped in the assassination of Mary’s first husband, something he swore to her that he had no knowledge of. Worse yet, he turned on his own men, “throwing them to the dogs”, which among other things, led to his exile in 1567 and eventually, imprisonment.

With a country in utter disrepair and increased feuding, rumors ran rampant that Mary not only knew about her first husband’s murder but was part of it. Also, she was accused of being a harlot and sleeping with James while Darnley was still alive, (a fact that has been disputed for complete lack of proof). Everyone was turning on everyone, and she could no longer trust those within her court. In the meantime, Moray, took control of the Scottish throne, after also deceiving his half-sister. Mary had no choice but to run and to England she fled, praying that her Catholic adherents, including the pope, would come to her aid and rescue. It did not happen.

However, once in England, she would be an outcast and live in a series of households as a prisoner over the next eighteen years. It was during this period that Mary’s health worsened due to lack of exercise (she was always fond of hunting, riding and walking). She was under constant supervision ordered by Cecil, who continued to look for proof of her egregious “errors” including the death of Henry Stuart, (he was convinced of her guilt). To be honest, he didn’t care if she was or wasn’t guilty of any crime, he would simply find the right people to supply him with the “facts”.

While Elizabeth was happy to keep Mary under captivity and watchful eyes, one thing she did not want to do was to have her beheaded. Why, you ask? Simple, because it would set a precedent against her and future monarchs. Then, ascension to the throne was considered a God-given right, that no man could put asunder. It would be regicide, a fact that Elizabeth could not endure or accept, and she made it clear to Cecil. However, he ignored his queen and went about his final plan to abolish Mary’s rule.

Nonetheless, one thing that Elizabeth could not dismiss were the English who still held onto Catholicism. As long as Mary was alive, there was hope that she would replace the Protestant queen, and there was talk among her countrymen of her own assassination, replacing her with her cousin and now natural enemy. Mary would always be a threat. What would Elizabeth do? She was in constant turmoil.

Finally, in the year, 1587, despite the fact that she was a sovereign queen of another country, Cecil pulled every trick in the book – Mary was condemned and put to death by sword. A sad ending to what was a glorious and promising beginning in France at the age of five.

Not only am I convinced that Mary was doomed from the beginning (even though she made questionable decisions later in life), but I’m also dismayed by Elizabeth’s frequent change of mind and heart during the reign and fall of her cousin. One moment she was writing loving letters to Mary and the next, she was threatening her and trying to take control of everything she did. Often her vacillations would change within days, then back again.

Although she held onto her belief and convictions, never taking a husband to rule alongside her (who could blame her after she saw what her father, Henry the VIII did during his scandalous reign) she nonetheless kept Cecil in his post in which he took advantage of her through his dastardly deeds. While she was unaware of many of his dealings, she knew what he was capable of once he set his mind. How could a powerful, independent, and intelligent woman continue to be swayed by his guidance? This will always perplex me.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.